Union Budget + Gaganyaan = India's Space Station.

Total Views |

The Union Budget presented to the parliament yesterday must be a special one for the Department of Space (DoS). Special because it is the first financial allocation to DoS in an extremely crucial decade for the global economy, the first after the ham-fisted impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the global economy, and the first after the far-reaching Aatmanirbhar Bharat reforms initiated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi's administration.

The space budget has made a generally favorable impression. The finance ministry ensured no reductions to the space budget, apportioned a substantial sum to space sector commercialization efforts in the light of the space reforms of May 2020, but balanced it out unfortunately by not allocating any significant capital for other new space projects. While juggling with these variables, the Narendra Modi administration has affixed its eyes on Gaganyaan. And that means a lot.

The DoS demand for grants has grown from 13479 crores in 2020-21 to 13949 crores in 2021-22. A dominant fraction of this growth is the 700 crores earmarked for the DoS-governed public-sector company known as the New Space India Limited (NSIL). The NSIL is the government's nodal agency for constructing the Polar Synchronous Launch Vehicle (PSLV) under a public-private consortium consisting of space contractors like Godrej Aerospace, Hindustan Aeronautics Limited, Larsen and Toubro, and others. The consortium-approach for constructing PSLV has been in the works for a decade, and NSIL is mandated to fructify it. Likewise, the NSIL will be central to the consortium to build the next-generation Small Satellite Launch Vehicle (SSLV). NSIL will also offer various launch options for satellite and space subsystems sector clientele and, more importantly, commercialize technology spin-offs from all the DoS laboratories, including ISRO. With a large allocation of 700 crores, it is evident that the government is serious about commercializing the national civilian space program and monetizing it.

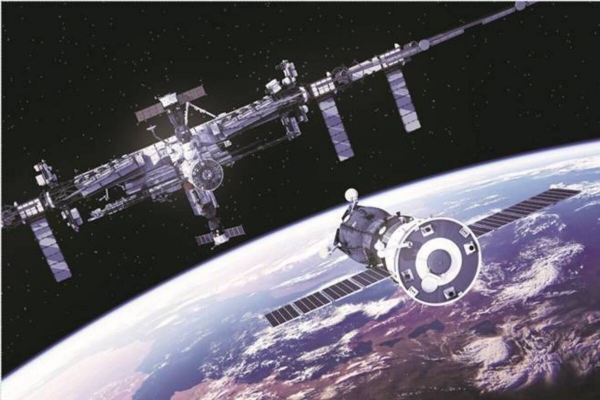

As one of the world's top five economies, and the fastest-growing one, India is far behind its other four peers in commercializing the national civilian space program. Take, for example, in 2019, the United States was able to send astronauts to the International Space Station (ISS) on a privately-built launch vehicle – the SpaceX Falcon-Heavy – and a privately built human-rated space-capsule – the SpaceX Crew Dragon. After an intense evaluation and commercial contest, these two products were selected, which means companies are equivalent to SpaceX teeming in the U.S. space ecosystem. This extensive private sector involvement was possible because the U.S. space agency, NASA, made a policy to encourage private sector participation in human spaceflight through the Commercial Orbital Transportation Services for launch vehicles services, Commercial Resupply Services for supplies and logistics, and Commercial Crew Program for human transportation. The Russian company, GLAVKOSMOS, which works under its space agency Roscosmos, has long reaped the profits of commercializing the human-rated Soyuz-2 launch vehicle, particularly for flights to the ISS.

China has acquired proficiency in human spaceflight with its Shenzhou program that witnessed the first crewed mission in 2003. It is about to start constructing its modular space station in the low-Earth orbit. It will become the only country to operate a nationalized space station as the ISS is shared between five partners, U.S., Russia, Japan, Europe, and Canada. The Chinese will use its space station as a diplomatic contraption and attract countries and companies aligned with its aggressive geopolitical goals.

In December 2020, the European Space Agency, NASA, and many other space agencies that have endorsed the U.S.-led Artemis Accords to go to the Moon jointly had signed a memorandum of understanding to build the first human-rated space station in the orbit of the Moon deemed as the GATEWAY. All these developments hint towards the progressing use of low-Earth orbits for commercial and national space stations. In contrast, the West that has long operated in the low-Earth orbit with the ISS is now graduating to the Moon.

Therefore, these fast-paced movements make it extremely critical for India to execute Gaganyaan on time and demonstrate capsule capability in the next 2-3 years. Gaganyaan is not a vanity project, neither a pet project of the Modi administration, nor can it be considered a one-off technology demonstrator. It is exceptionally strategic and should be treated as a precursor to India's space station, which should come up by the end of the 2020s. To realize such a space station, the government should identify both public and private sector companies that can become part of the Indian space station well in advance. In that regard, the space reforms of May 2020 and the allocations to the NSIL also seem timely. The decade of 2020s is decisive for the Indian space program as it sheds its Soviet-era hangover and becomes a tour-de-force suiting the third-largest economy of the world.