Space Station: India-China, Score 0-1, Game has just begun

Total Views |

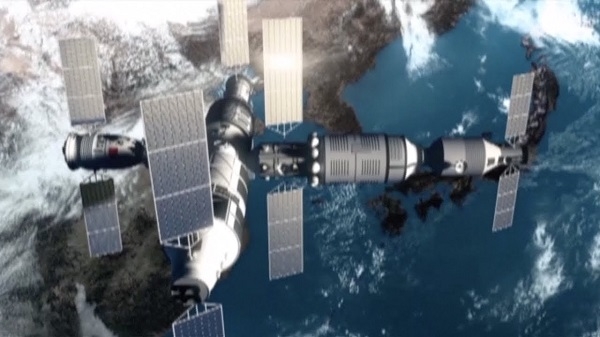

April 29, 2021, the third-largest launch vehicle in the world, the Long March 5, decorated with a large CMS (China Manned Space) logo, carried the first and core module, Tianhe-1, of the Large Modular Chinese Space Station. China’s today’s accomplishment is the culmination of its aim that it had set eyes on in 1992 when it was merely a US$ 430 billion economy. To put into perspective, India, at this stage, when it has initiated human spaceflight, is zooming towards a US$ 4 trillion economy mark.

China carved its independent path in 1992 when its State Council initiated Project 921, which focused on national capacity-building in human spaceflight. During the same period, the United States (US) and Russia, newly reconstituted from the Soviet Union, merged their separate space station plans. The new partnership then attracted additional investments from Japan, Canada, and the European Space Agency. The collaboration, now known as the International Space Station (ISS), raised its first module in 1998.

Although China remained away from the ISS, its first human spaceflight demonstration, akin to India’s under-preparation Gaganyaan, known in their case as Shenzhou, happened immediately in 2003. Their first spacewalk, where the taikonauts demonstrated operations outside the space capsule, occurred in 2011. Their first module-docking demonstration occurred in 2016. It took 29 years for China to come full circle today. The credit for it goes to the deep linkages between multiple Chinese stakeholders. The CMS, lead of the Chinese human spaceflight program, is an agency of the Equipment Development Department of the Central Military Commission. The People’s Liberation Army Strategic Support Force is the overseer of most ground-based space assets of China. The People’s Liberation Army Air Force trains the taikonauts. The Chinese Academy of Sciences provides it the R&D support. The State Council facilitates the program access to the comprehensive space-military industrial complex in China.

With China’s Tianhe-1 launch, there is an increasing sense between space-faring nations to have nationally-owned assets in the low-Earth orbit. These assets will be available to entities friendly to the station owners. Still, the larger picture is, geopolitical multipolarity has now been extended to the low-Earth orbit (LEO). The US has already chosen two commercial entities, Axiom Space and Bigelow Aerospace, to build US-governed space stations in LEO. The Russian-governed LEO space station plan is mature. After dissociating with the ISS, sometime around 2024-25, Russia may immediately secure an LEO presence, putting all its human spaceflight experience, spanning from the Mir- and Salyut-era, at work. However, the international cooperation witnessed in the LEO all these years is now being taken to the Moon. China has joined hands with Russia to build the International Scientific Lunar Station (ISLS), which will consist of research facilities orbiting the Moon and present on the Moon’s surface. Similarly, the US and its nine Artemis Accords partners – Canada, Brazil, United Kingdom, Luxembourg, Italy, Ukraine, United Arab Emirates, Australia, and Japan - plan to build a lunar orbiting Lunar Gateway station. These station will be an essential conduit to each of these groupings scientific and techno-economic activities on the Moon. Moreover, these projects will be vital bonds of international diplomacy in the coming years.

Where should India find itself in this growing interest for human spaceflight? Firstly, we must view Gaganyaan as a much-delayed but essential step ahead in the direction of building and operating an Indian space station. New Delhi will have to quickly follow Gaganyaan up with a spacewalk demonstration, a large-module docking experiment, long-duration human spaceflight, to finally reach the space station launch stage. India certainly cannot pursue these crucial stages leisurely the way the US, Russia, and China did. Space activities globally are seeing tremendous private sector participation. This was not the case when the Americans, Russians, Europeans, Japanese, and Chinese attained space station module construction competence. Today, as India marches in the same direction, the business rules are already laid out. Investors, be it governments or private entities, would not wait for decades for the return-on-investments.

India should aim to complete the three-decade cycle that China took to build the space station within 10-15 years. Doing so, New Delhi must look to rouse interest in all the possible industry stakeholders. Pharmaceuticals, advanced materials, robotics, artificial intelligence, Industry 4.0, software, high-technology manufacturing, specialty chemicals are the untapped stakeholders. These stakeholders are consequential force-multipliers in India’s pursuit to become a five-trillion dollar plus economy. Their force-multiplying ability can only be harnessed if these stakeholders are given an opportunity to catapult in their respective domains. Space innovation is the motherlode of catapulting innovation and industrialization. Had that not been the case, no superpower would have invested resources in it. These disparate stakeholders can be brought together if a competitive space ecosystem is put in place. The teeming ecosystem can entail academia, the space agencies, ISRO and IN-SPACE, the armed forces, industry, startups, and think tanks revolving as electrons around the government’s nucleus.

There is no reason for India to pursue its space station plans lethargically, blaming it on the noise in the democracy. This will give China an excuse to sell its autocratic model in a convincing way. India can attain its own space station in a short span of time if stakeholders shun their short-sighted, self-serving interests and cancel the unyielding noise. For now, kudos to China. The score is 0-1, but the game has just begun.

.

.